Under the suggestion of many peers, I began reading Research Talks: Motivating Acquisition-Centered Classrooms by Eric Herman earlier this school year.

Although organized to be read over the course of each week in a school year, my schedule didn’t quite allow for that and so I read as I was able. I took time between readings to digest the quotes as suggested and highlighted important or meaningful quotes to me as I went along.

What follows here are three (really, four) of the quotes from the first 15 weeks which spoke loudest to me and my reflection on those quotes.

- “(1) all classroom activities should be devoted to communication with focus on content, (2) no speech errors should be corrected, and (3) students should feel free to respond in L1, L2, or any mixture of the two” [p. 5; Krashen, S. D. & Terrell, T. D. (1983). The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. Hayward, CA: Alemany Press. p. 331-332]

- “No longer the necessary vehicle by which to access interesting subject matter, Latin was reduced at best to a linguistic puzzle or a challenging mental exercise, and at worst to a dull catalogue of abstract, nonsensical rules.” [p. 19; Musumeci, D. (2009). History of Language Teaching. In M. H. Long & C. J. Doughty (Eds.), The handbook of language teaching (pp. 42-62). Oxford, England: Blackwell. p. 54] and “focus on forms tends to produce boring lessons, with resulting declines in motivation, attention, and student enrollments.” [p. 26; Long, M. H. (2000). Focus on form in task-based languge teaching. In R. L. Lambert & E. Shohamy (Eds.), Language policy and pedagogy (pp. 179-92). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins. p. 182]

- “Choosing activities and content that are highly engaging increases participation and effort during the activity… We like to do what we enjoy and what we are good at. The ultimate result in intrinsic motivation.” [p. 73; ellipsis by me]

For the first quote to make sense, as a Latin teacher, I had to accept and agree with the idea that communication is not solely speech. Communication happens whenever two or more people are sharing ideas, opinions, and thoughts. That can, and frequently, does include speech, but might also include writing, listening, and reading. And, just because something is spoken aloud, doesn’t automatically mean it is communication. I know of quite a few people who speak even when no one else is around. So, in understanding the first quote, let’s agree that communication is the sharing of ideas, opinions, and thoughts, whether that be through speaking, writing, listening, or reading. Secondly, let’s agree that part two of that first quote doesn’t just mean speech shouldn’t be corrected, but neither should any attempt at continuing the conversation.

Now, onto my reflection:

The trap of Latin is that it frequently attracts folks obsessed, even if only a little, with puzzles and rules. Most of us who became Latin teachers, did so because we enjoyed the puzzle of piecing long, complex sentences together into a well-said thought from the ancients. We enjoyed those grammar charts, myriad of rules and exceptions, and the literal detective work of applying which, when, and where.

Too bad most of our students aren’t the same.

Instead, our focus on those forms which so excited and compelled us, so often de-motivates and frustrates those we are teaching. No matter how much we try to convey our love for the intricacies of the language to the students before us, unless they too are one of the rare few stirred by the linguistic puzzle, it will always fall flat.

Students want to communicate. That is literally what they spend their free time doing – messaging, snapchats, memes, tik tok, etc. Students don’t care about spelling and grammar the same way many of their teachers do. It is the message that matters, not the form of it. Who cares if I use text short-hand, an emoji or gif, or even correct capitalization? You understand. You reply. Communication.

Our focus, then, on the forms does exactly as the quote purports: it creates boring lessons, a lack of motivation in our students, and lower enrollment numbers.

I’ve seen it first hand. My enrollment, which peaked eight or nine years ago with two full time Latin teachers in the same school building, has now fallen to one part-time teacher. I was not changing with the times. I did not realize that my obsessed attention to form over communication drove students away from a language, already considered dead and not communicative, towards those viewed as more communicative, i.e. Spanish, German, and French.

Who wants to learn how to decline a 3rd declension i-stem noun when you could be watching Disney films in Spanish?

So, how to bring those students back?

First, Latin needs to once again become the language with which to access interesting content. Not the grammatical rules, but real, authentic subject matter. Cultural stuff. The stuff we teachers frequently resorted to teaching in English, as a break from all those grammar charts.

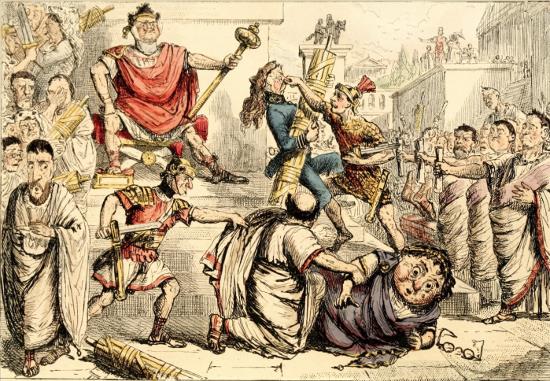

We need to start teaching the content, the culture in Latin. No more PowerPoints in English about the seven kings of Rome… but, a picture

Tarquinius Superbus makes himself King by John Leech

and a few questions

- What is happening in this picture? Why is it happening?

- Who do you connect with most in this picture? Why? In what way?

- If this were a scene in a movie, who would play which part? Why?

- What happened before this scene? After this scene?

Just imagine how your students would answer these questions. What other questions would they ask you? Would they want to know more? Mine would. There would not only be more questions, but outright debate. My students, and I dare say yours too, would much rather talk about this picture than copy notes from a PowerPoint for a quiz or create their own poster of facts to share with their classmates.

And, all of this COMMUNICATION done in Latin. Well, at least from you, the teacher. Students should be allowed to answer and communicate with each other in whichever language they want. But, and this is a strong but, we could have planned for this and already introduced some language which students would find useful in discussing this picture and topic in Latin, if they wanted. And, if done right, this “first step” communication about a picture could lead to a co-created text about the Roman kings which the students would then use to move into more and more communication in Latin about the content.

[Information on the image: A graphic representation of the foreign language assessment framework from the National Association of Educational Progress; as shared and discussed by James Hosler]

This type of content-based instruction, with a focus on comprehensible input, builds upon the foundation and warning contained within those quotes (really, within that research).

My final point:

If we want intrinsically motivated students, engaged and eager to learn, in our classes, we must move away from the teaching of Latin through forms and toward the teaching of Latin through content based around communication and not correction.